Wednesday 15th May 2024

Climate Accounting as a Competitive Edge

This is an abbreviated version of an article written by Per Espen Stoknes

and Elisa Dahl Walderhaug, published in Magma (Issue 4, 2023).

What’s the state of climate accounting in Norwegian companies? What obstacles do they encounter, and what competitive advantages exist?

Climate accounting is becoming a central part of corporate strategy, with assessments of environmental and social financial risk into integrated reporting (Gleeson-White, 2015). Since 2020, we have seen an increasing proportion of investors both expect and demand such standardized ESG from companies. But it is only when a company has compiled climate accounts over several years that it can analyze relevant, i.e., both risk-reducing and opportunity-creating measures to achieve a climate goal.

Some statistics:

Research indicates that in 2022, 85 out of Norway's hundred largest companies submitted climate accounts.

The quality of these reports and goals varies: More than half (56 percent) of the 300 largest companies in the Nordic region either provided only the absolute minimum information on indirect emissions in their 2022 reports or completely lacked such disclosure (PwC, 2021, 2022; The Governance Group, 2021; Position Green, 2022).

Furthermore, over 9,000 large and small enterprises in Norway hold certification as Environmental Lighthouses and subsequently develop simple climate accounts (Environmental Lighthouse, 2022). However, a mere 33 percent had climate accounts according to a survey conducted by the auditing firm EY (EY, 2019). Nonetheless, there are also compelling reasons (such as increased turnover among providers of climate accounts) to believe that the proportion of smaller companies adopting such measures is steadily rising, particularly in recent years.

Why do climate accounts?

Our definition of climate accounting is as follows: It’s a tool that tracks all greenhouse gas emissions from a company's value chain over time.

The primary departure from conventional accounting lies in the choice of measurement unit, which isn’t in currency but in tons of CO2 equivalents (tCO2e). This approach captures historical emissions data across various sectors in a consistent way. And can assess the success of ongoing improvements.

Good climate accounts can point out the need for risk mitigation and emission reduction in the future, while also identifying new and greener business opportunities. It empowers companies to map how their diverse activities influence both stakeholders, nature, and the climate, pinpointing the most effective areas for intervention. Developing a climate account solely for a single year is of limited value; it is primarily a long-term tool for evaluation.

Benefits and competitive advantages:

• Enhance operational efficiency within your own business in terms of energy, materials, and finances.

• Bolster your brand resilience in the marketplace and among customers

• Foster transparent, fact-based, and trust-inspiring communication with customers or investors.

• Provide more affordable access to capital (loans and investors).

• Increase awareness of emissions associated with day-to-day activities.

• Identify and manage financial risk.

• Stay ahead of regulatory changes and reduce regulatory risks.

• Form the basis for climate and business strategy with goals that express how forward-looking you want to be.

• Ensure accountability within your organization, focusing efforts on areas with the greatest potential for emissions reduction.

• Introduce routines and procedures that streamline employee consideration of climate factors in procurement processes.

• Motivate and equip employees with the necessary knowledge to factor climate considerations into procurement decisions.

• Prevent and reduce waste of energy and materials.

• Map whether the supplier chain aligns with climate-related criteria.

• Long-term lower expenses and associated fees.

Many companies implement climate accounts without a clear understanding of the underlying rationale, often merely in response to external expectations from customers, public regulations (CSRD/SFDR), or investor requests. Consequently, the establishment of climate accounts may entail the formation of a small team or sustainability officer tasked with the singular objective of "ESG-reporting," often disconnected from broader strategic objectives. As a result, they inadvertently limit the potential competitive advantages to only a subset of the opportunities outlined above.

However, well-executed climate accounts can serve useful functions beyond its immediate climate-related scope. It frequently serves as a conduit for transferring data to broader resource productivity analyses, including the usage of scarce resources or materials like plastics. Furthermore, the data can be leveraged within internal tools for waste management, circular consumption practices, economic modeling, and risk assessment concerning locations, societal contexts, and logistical efficiencies.

For companies aiming to mitigate waste across their entire value chain or evaluate suppliers based on their climate impact, maintaining both consumption and climate accounts proves invaluable. Moreover, the climate account can encompass an enhanced energy audit, delineating the proportions of renewable and fossil energy sources utilized. It also provides insights into the most environmentally favorable locations for production activities worldwide, considering climate-related risks.

In addition, you can measure consumption of everything you buy and sell of products and services. Not least, it enables broader stakeholder management.

Challenges in Climate Accounting

Drawing from our own long experience (with approximately 800 customers at Cemasys and hundreds of master's theses from BI Executive Green Growth programmes), the current challenges for Norwegian companies include: • Inaccurate measurements of internal consumption data on a monthly basis.

• Varied methodologies for estimating emissions in cases where consumption data is unavailable.

• Limited transparency from suppliers resulting in insufficient access to supplier data.

• Lack of methodological consistency and variation in data sourcesand methodologies from year to year.

• Limited availability or access to standardized emission factors.

• Inadequate reporting tools (using Excel sheets often yield inconsistency errors).

• Limited understanding of value chain emissions (Scope 3) and inconsistency over time.

The current state for Norwegian companies’ climate accounts in 2023 reveals the need for many to actively engage in reduction measures and broaden the scope beyond their own operations, a trend supported by surveys conducted by PwC (2023) and Position Green (2023).

What are the benefits of ambitious climate goals?

In today's landscape, stakeholders increasingly seek to comprehend the climate strategies of the companies they invest in or procure from. They demand transparency regarding goals, initiatives, and actual emission reductions. The potency of a climate goal lies in its ability to delineate the ambition to enact measures. External benchmark indices, such as ESG ratings, now exert pressure on companies to establish and disclose climate goals. Crucially, ambitious, and credible climate goals signify strategic, long-term vision and leadership, thereby enhancing reputation among investors and customers. Such goals align the company with scientific findings and European and national policies.

The ambition must be contextualized within the broader framework; the EU aims to reduce emissions by 60 percent by 2030, while Norway targets reductions of 55 percent by 2030 and 95 percent by 2050, all benchmarked against the 1990 baseline. Given their historical responsibility for climate change, political stability, technological capabilities, and stronger economies, industrialized nations bear the primary burden of emission reductions. However, since 2014, the EU has progressively tightened its standards (CSRD, Taxonomy, SFDR), becoming applicable to many Norwegian entities from 2023 onwards. Soon (by 2028) all European companies must comply.

How to calculate emissions reductions to achieve goals

To achieve climate goals, it's imperative to outline all measures in a business case. The business case should make future impacts on profits, risk, and emissions clear. This approach allows for the quantification of different measures so they can be prioritized and scaled.

Such assessments enable alignment of the company's climate strategy and action plan with expected goal attainment over time. If the impact of implemented measures falls short of achieving emission goals, reassessment of further emission reduction measures is warranted. The last emissions reductions tend to be the most costly, when using incremental approaches. For larger gains, systemic approach to to emerging technologies and innovations, particularly those related to replacing end-user consumption with smarter solutions.

On an annual basis, it's essential to conduct new measurements to gauge whether current activities are progressing toward goal achievement based on the planned measures. This approach is instrumental in realizing climate objectives, as several well-designed climate strategies only become quantifiable when assessed annually, considering changes in activities and progress towards goals over time. This methodology parallels traditional financial accounting practices and can be roughly likened to tracking progress towards financial objectives such as higher revenues, lower risk or cost reductions.

What are the current challenges in setting climate goals?

When companies and corporate structures change, it can be a challenge to maintain relevance for their Science-Based Targets (SBT). These require constant adjustment to remain affective, and a significant challenge arises in recalibrating the start year or base year in response to changes. Although GHG has developed a standardized process for this purpose, awareness, and adherence to it remain limited. To address this challenge, companies should establish clear guidelines for calculating emissions based on the year and articulate the rationale and context for any recalculation. Additionally, defining a threshold value to trigger base year recalibration is essential. Retroactively recalculating emissions in the base year helps ensure the consistency and relevance of the goal amidst structural changes withing the company.

Structural changes encompass various scenarios, including mergers, acquisitions, divestments, outsourcing of emission activities, and alterations in calculation methodologies or improvements in data accuracy. While individual structural changes may not significantly impact base year emissions, the cumulative effects of multiple minor changes could warrant adjustments.

Base emissions and historical data should not be recalculated due to organic growth or decline. Organic growth or decline refers to increases or reductions in production output, changes in product mix, and the opening or closure of operating units owned or controlled by the company. This distinction is crucial as organic growth or decline directly influences the company's emission profile over time and must be accounted for accordingly.

Economic growth or emission cuts?

Many companies face a dilemma: they strive for both rapid (organic) economic growth and for lower emissions. But even with revolutionary improvements, setting up new large facilities typically leads to increased emissions, particularly in the beginning. Yet, a green transition can only happen if the most efficient companies expand, outcompete and replace older, wasteful ones. Therefore, to stay solely focused on emission reductions targets (such as an SBTi absolute target), can be counter-productive in view of the economy as a whole. From a purely reduction-focused viewpoint, ceasing all activity would seem optimal (ie. “degrowth” – which don't align well with boards and executives).

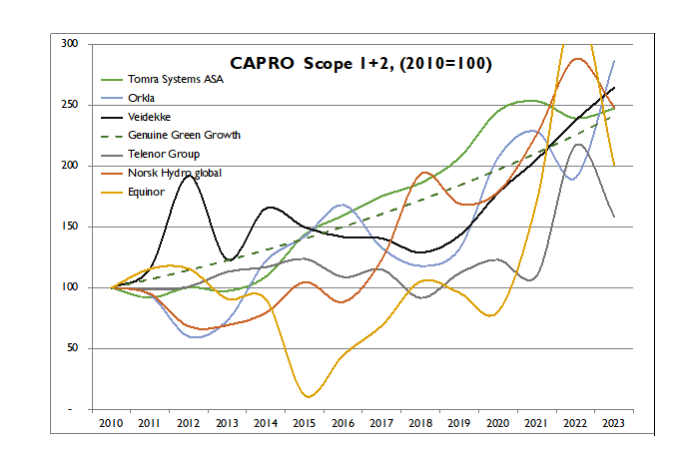

On a global scale, the overarching goal is twofold: sustaining economic growth while rapidly reducing greenhouse gas emissions. To stay below a 2°C rise, emissions must decouple from value creation by at least 5% annually from 2020. To achieve a 1.5°C target, this decoupling needs to exceed 7% yearly (Grubler et al., 2018; Stoknes, 2019; Stoknes & Rockström, 2018). Hence, a carbon productivity ("capro”) goal is essential: creating more value-added with fewer emissions. Companies setting such goals above +7% annually can not only become growth leaders but also improve carbon productivity across the economy. This avoids the trade-off between growth and emissions by focusing on a win-win perspective: With a Genuine Green Growth strategy, you can achieve both (Stoknes, 2021). Some Norwegian companies have delivered >7% average every year since 2010, see figure 1.

Another significant challenge arises when previously unmeasured emissions are added, termed additionality (particularly in scope 3). Or when merger, acquisitions or sales of business units within the group occurs. These events can disrupt longer data series unless all emissions are adjusted back to a new base year.

Conclusion

The purpose of setting a green growth climate goal lies in a company's commitment to reducing emissions sufficiently while also expanding its market share. This can be achieved by moving up the “green growth stairs” model, as outlined in Tomorrow’s Economy (Stoknes 2021). Aligning business goals with standards and science-based targets is crucial for future investor and customer acceptance. However, many businesses struggle to define and internalize science-based climate goals, indicating a need for further research and knowledge development to overcome barriers and integrate these goals effectively into the core strategy.

Read more in: Stoknes (2021), Tomorrow’s Economy, particularly chapters 5-8.

– Per Espen Stoknes weaves together psychology and economics in imaginative ways, often revolving around our human relationships to the natural world and to each other.

― TED Global